12 Python Decorators to Take Your Code to the Next Level

Table of contents

Do more things with less code without compromising on quality.

Python decorators are powerful tools that help you produce clean, reusable, and maintainable code.

I’ve long waited to learn about these abstractions and now that I’ve acquired a solid understanding, I’m writing this story as a practical guide to help you, too, grasp the concepts behind these objects.

No big intros or lengthy theoretical definitions today.

This post is rather a documented list of 12 helpful decorators I regularly use in my projects to extend my code with extra functionalities.

We’ll dive into each decorator, look at the code and play with some hands-on examples.

If you’re a Python developer, this post will extend your toolbox with helpful scripts to increase your productivity and avoid code duplication.

Less talk, I suggest we jump into the code now 💻.

New to Medium? You can subscribe for $5 per month and unlock an unlimited number of articles I write on programming, MLOps and system design to help data scientists (or ML engineers) produce better code.

1 — @logger (to get started)✏️

If you’re new to decorators, you can think of them as functions that take functions as input and extend their functionalities without altering their primary purpose.

Let’s start with a simple decorator that extends a function by logging when it starts and ends executing.

The result of the function being decorated would look like this:

some_function(args)

# ----- some_function: start -----

# some_function executing

# ----- some_function: end -----

To write this decroator, you first have to pick an appropriate name: let’s call it logger.

logger is a function that takes a function as input and returns a function as output. The output function is usually an extended version of the input. In our case, we want the output function to surround the call of the input function with start and end statements.

Since we don’t know what arguments the input function use, we can pass them from the wrapper function using args and *kwargs. These expressions allow passing an arbitrary number of positional and keyword arguments.

Here’s a simple implementation of the logger decorator:

def logger(function):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print(f"----- {function.__name__}: start -----")

output = function(*args, **kwargs)

print(f"----- {function.__name__}: end -----")

return output

return wrapper

Now you can apply logger to some_function or any other function for that matter.

decorated_function = logger(some_function)

Python provides a more pythonic syntax for this, it uses the @ symbol.

@logger

def some_function(text):

print(text)

some_function("first test")

# ----- some_function: start -----

# first test

# ----- some_function: end -----

some_function("second test")

# ----- some_function: start -----

# second test

# ----- some_function: end -----

2 — @wraps 🎁

This decorator updates the wrapper function to look like the original function and inherit its name and properties.

To understand what @wraps does and why you should use it, let’s take the previous decorator and apply it to a simple function that adds two numbers.

(This decorator doesn’t use @wraps yet)

def logger(function):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

"""wrapper documentation"""

print(f"----- {function.__name__}: start -----")

output = function(*args, **kwargs)

print(f"----- {function.__name__}: end -----")

return output

return wrapper

@logger

def add_two_numbers(a, b):

"""this function adds two numbers"""

return a + b

If we check the name and the documentation of the decorated function add_two_numbers by calling the __name__ and __doc__ attributes, we get … unnatural (and yet expected) results:

add_two_numbers.__name__

'wrapper'

add_two_numbers.__doc__

'wrapper documentation'

We get the wrapper name and documentation instead ⚠️

This is an undesirable result. We want to keep the original function’s name and documentation. That’s when the @wraps decorator comes in handy.

All you have to do is decorate the wrapper function.

from functools import wraps

def logger(function):

@wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

"""wrapper documentation"""

print(f"----- {function.__name__}: start -----")

output = function(*args, **kwargs)

print(f"----- {function.__name__}: end -----")

return output

return wrapper

@logger

def add_two_numbers(a, b):

"""this function adds two numbers"""

return a + b

By rechecking the name and the documentation, we see the original function’s metadata.

add_two_numbers.__name__

# 'add_two_numbers'

add_two_numbers.__doc__

# 'this function adds two numbers'

3 — @lru_cache 💨

This is a built-in decorator that you can import from functools .

It caches the return values of a function, using a least-recently-used (LRU) algorithm to discard the least-used values when the cache is full.

I typically use this decorator for long-running tasks that don’t change the output with the same input like querying a database, requesting a static remote web page, or running some heavy processing.

In the following example, I use lru_cache to decorate a function that simulates some processing. Then, I apply the function on the same input multiple times in a row.

import random

import time

from functools import lru_cache

@lru_cache(maxsize=None)

def heavy_processing(n):

sleep_time = n + random.random()

time.sleep(sleep_time)

# first time

%%time

heavy_processing(0)

# CPU times: user 363 µs, sys: 727 µs, total: 1.09 ms

# Wall time: 694 ms

# second time

%%time

heavy_processing(0)

# CPU times: user 4 µs, sys: 0 ns, total: 4 µs

# Wall time: 8.11 µs

# third time

%%time

heavy_processing(0)

# CPU times: user 5 µs, sys: 1 µs, total: 6 µs

# Wall time: 7.15 µs

If you want to implement a cache decorator yourself from scratch, here’s how you’d do it:

You add an empty dictionary as an attribute to the wrapper function to store previously computed values by the input function

When calling the input function, you first check if its arguments are present in the cache. If it’s the case, return the result. Otherwise, compute it and put it in the cache.

from functools import wraps

def cache(function):

@wraps(function)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

cache_key = args + tuple(kwargs.items())

if cache_key in wrapper.cache:

output = wrapper.cache[cache_key]

else:

output = function(*args)

wrapper.cache[cache_key] = output

return output

wrapper.cache = dict()

return wrapper

@cache

def heavy_processing(n):

sleep_time = n + random.random()

time.sleep(sleep_time)

%%time

heavy_processing(1)

# CPU times: user 446 µs, sys: 864 µs, total: 1.31 ms

# Wall time: 1.06 s

%%time

heavy_processing(1)

# CPU times: user 11 µs, sys: 0 ns, total: 11 µs

# Wall time: 13.1 µs

4 — @repeat 🔁

This decorator causes a function to be called multiple times in a row.

This can be useful for debugging purposes, stress tests, or automating the repetition of multiple tasks.

Unlike the previous decorators, this one expects an input parameter.

def repeat(number_of_times):

def decorate(func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

for _ in range(number_of_times):

func(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

return decorate

The following example defines a decorator called repeat that takes a number of times as an argument. The decorator then defines a function called wrapper that is wrapped around the function being decorated. The wrapper function calls the decorated function a number of times equal to the specified number.

@repeat(5)

def dummy():

print("hello")

dummy()

# hello

# hello

# hello

# hello

# hello

5 — @timeit ⏲️

This decorator measures the execution time of a function and prints the result: this serves as debugging or monitoring.

In the following snippet, the timeit decorator measures the time it takes for the process_data function to execute and prints out the elapsed time in seconds.

import time

from functools import wraps

def timeit(func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.perf_counter()

print(f'{func.__name__} took {end - start:.6f} seconds to complete')

return result

return wrapper

@timeit

def process_data():

time.sleep(1)

process_data()

# process_data took 1.000012 seconds to complete

6 — @retry 🔁

This decorator forces a function to retry a number of times when it encounters an exception.

It takes three arguments: the number of retries, the exception to catch and retry on, and the sleep time between retries.

It works like this:

The wrapper function starts a for-loop of

num_retriesiterations.At each iteration, it calls the input function in a try/except block. When the call is successful, it breaks the loop and returns the result. Otherwise, it sleeps for sleep_time seconds and proceeds to the next iteration.

When the function call is not successful after the for loop ends, the wrapper function raises the exception.

import random

import time

from functools import wraps

def retry(num_retries, exception_to_check, sleep_time=0):

"""

Decorator that retries the execution of a function if it raises a specific exception.

"""

def decorate(func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

for i in range(1, num_retries+1):

try:

return func(*args, **kwargs)

except exception_to_check as e:

print(f"{func.__name__} raised {e.__class__.__name__}. Retrying...")

if i < num_retries:

time.sleep(sleep_time)

# Raise the exception if the function was not successful after the specified number of retries

raise e

return wrapper

return decorate

@retry(num_retries=3, exception_to_check=ValueError, sleep_time=1)

def random_value():

value = random.randint(1, 5)

if value == 3:

raise ValueError("Value cannot be 3")

return value

random_value()

# random_value raised ValueError. Retrying...

# 1

random_value()

# 5

7 — @countcall 🔢

This decorator counts the number of times a function has been called.

This number is stored in the wrapper attribute count .

from functools import wraps

def countcall(func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

wrapper.count += 1

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print(f'{func.__name__} has been called {wrapper.count} times')

return result

wrapper.count = 0

return wrapper

@countcall

def process_data():

pass

process_data()

process_data has been called 1 times

process_data()

process_data has been called 2 times

process_data()

process_data has been called 3 times

8 — @rate_limited 🚧

This is a decorator that limits the rate at which a function can be called, by sleeping an amount of time if the function is called too frequently.

import time

from functools import wraps

def rate_limited(max_per_second):

min_interval = 1.0 / float(max_per_second)

def decorate(func):

last_time_called = [0.0]

@wraps(func)

def rate_limited_function(*args, **kargs):

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - last_time_called[0]

left_to_wait = min_interval - elapsed

if left_to_wait > 0:

time.sleep(left_to_wait)

ret = func(*args, **kargs)

last_time_called[0] = time.perf_counter()

return ret

return rate_limited_function

return decorate

The decorator works by measuring the time elapsed since the last call to the function and waiting for an appropriate amount of time if necessary to ensure that the rate limit is not exceeded. The waiting time is calculated as min_interval - elapsed, where min_interval is the minimum time interval (in seconds) between two function calls and elapsed is the time elapsed since the last call.

If the time elapsed is less than the minimum interval, the function waits for left_to_wait seconds before being executed again.

This function hence introduces a slight time overhead between the calls but ensures that the rate limit is not exceeded.

There’s also a third-party package that implements API rate limit: it’s called ratelimit.

pip install ratelimit

To use this package, simply decorate any function that makes an API call:

from ratelimit import limits

import requests

FIFTEEN_MINUTES = 900

@limits(calls=15, period=FIFTEEN_MINUTES)

def call_api(url):

response = requests.get(url)

if response.status_code != 200:

raise Exception('API response: {}'.format(response.status_code))

return response

If the decorated function is called more times than allowed a ratelimit.RateLimitException is raised.

To be able to handle this exception, you can use the sleep_and_retry decorator in combination with theratelimit decorator.

@sleep_and_retry

@limits(calls=15, period=FIFTEEN_MINUTES)

def call_api(url):

response = requests.get(url)

if response.status_code != 200:

raise Exception('API response: {}'.format(response.status_code))

return response

This causes the function to sleep the remaining amount of time before being executed again.

9 — @dataclass 🗂️

The @dataclass decorator in Python is used to decorate classes.

It automatically generates special methods such as __init__, __repr__, __eq__, __lt__, and __str__ for classes that primarily store data. This can reduce the boilerplate code and make the classes more readable and maintainable.

It also provides nifty methods off-the-shelf to represent objects nicely, convert them into JSON format, make them immutable, etc.

The @dataclass decorator was introduced in Python 3.7 and is available in the standard library.

from dataclasses import dataclass,

@dataclass

class Person:

first_name: str

last_name: str

age: int

job: str

def __eq__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, Person):

return self.age == other.age

return NotImplemented

def __lt__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, Person):

return self.age < other.age

return NotImplemented

john = Person(first_name="John",

last_name="Doe",

age=30,

job="doctor",)

anne = Person(first_name="Anne",

last_name="Smith",

age=40,

job="software engineer",)

print(john == anne)

# False

print(anne > john)

# True

asdict(anne)

#{'first_name': 'Anne',

# 'last_name': 'Smith',

# 'age': 40,

# 'job': 'software engineer'}

If you’re interested in dataclasses, you can check one of my previous articles.

10 — @register 🛑

If your Python script accidentally terminates and you still want to perform some tasks to save your work, perform cleanup or print a message, I find that the register decorator is quite handy in this context.

from atexit import register

@register

def terminate():

perform_some_cleanup()

print("Goodbye!")

while True:

print("Hello")

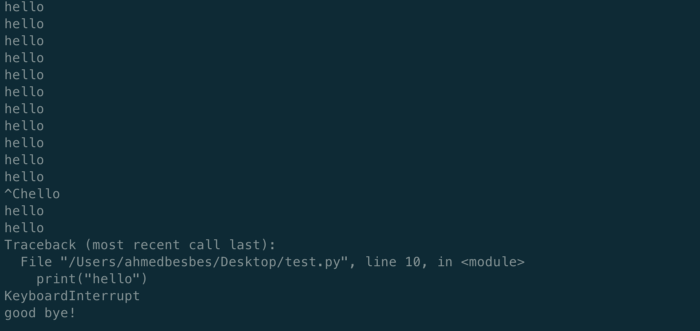

When running this script and hitting CTRL+C,

Screenshot by the user

we see the output of the terminate function.

11 — @property 🏠

The property decorator is used to define class properties which are essentially getter, setter, and deleter methods for a class instance attribute.

By using the property decorator, you can define a method as a class property and access it as if it were a class attribute, without calling the method explicitly.

This is useful if you want to add some constraints and validation logic around getting and setting a value.

In the following example, we define a setter on the rating property to enforce a constraint on the input (between 0 and 5).

class Movie:

def __init__(self, r):

self._rating = r

@property

def rating(self):

return self._rating

@rating.setter

def rating(self, r):

if 0 <= r <= 5:

self._rating = r

else:

raise ValueError("The movie rating must be between 0 and 5!")

batman = Movie(2.5)

batman.rating

# 2.5

batman.rating = 4

batman.rating

# 4

batman.rating = 10

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

# ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

# Input In [16], in <cell line: 1>()

# ----> 1 batman.rating = 10

# Input In [11], in Movie.rating(self, r)

# 12 self._rating = r

# 13 else:

# ---> 14 raise ValueError("The movie rating must be between 0 and 5!")

#

# ValueError: The movie rating must be between 0 and 5!

12 — @singledispatch

This decorator allows a function to have different implementations for different types of arguments.

from functools import singledispatch

@singledispatch

def fun(arg):

print("Called with a single argument")

@fun.register(int)

def _(arg):

print("Called with an integer")

@fun.register(list)

def _(arg):

print("Called with a list")

fun(1) # Prints "Called with an integer"

fun([1, 2, 3]) # Prints "Called with a list"

Conclusion

Decorators are useful abstractions to extend your code with extra functionalities like caching, automatic retry, rate limiting, logging, or turning your classes into supercharged data containers.

It doesn’t stop there though as you can be more creative and implement your custom decorators to solve very specific problems.

Here’s a list of awesome decorators to get inspired.

Thanks for reading!

Resources:

https://towardsdatascience.com/10-of-my-favorite-python-decorators-9f05c72d9e33

https://realpython.com/primer-on-python-decorators/#more-real-world-examples

follow me on my social media handles .